This week I’ll be revising my studio policy for the coming year. Every year, the process consists of iterating the document for the previous teaching year, making changes that involve rates, teachers, cancellation policies, and other small details (like parking on the correct side of the driveway and keeping your water bottle away from the piano).

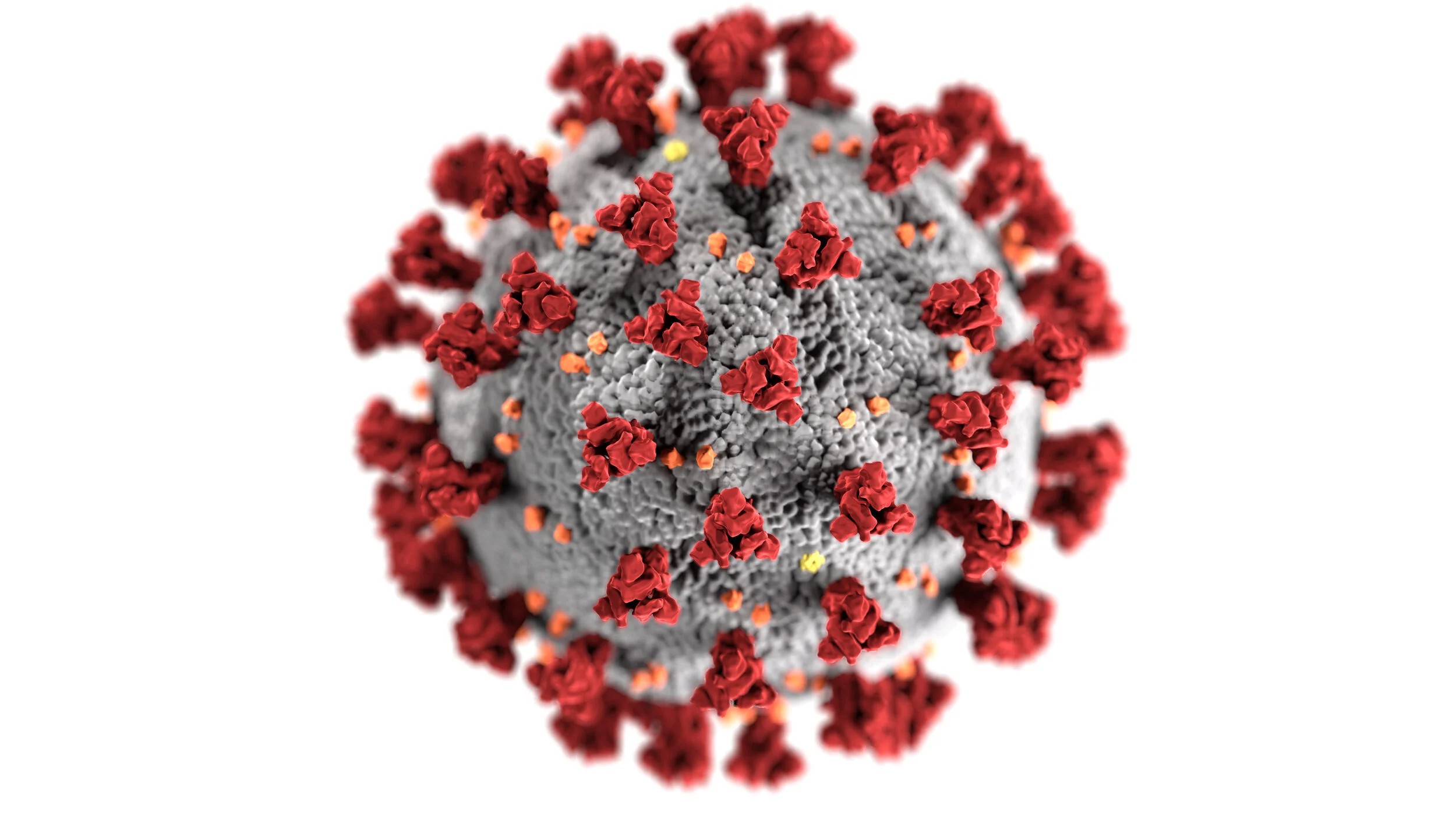

But this year, it’s a completely different reality. Most of us have already made the transition to full online teaching, and we now have to navigate how to communicate to parents the policies and procedures for dealing with a tremendous amount of uncertainty regarding the progress and transmission of the disease in our local areas.

Below are a few issues I’m working on for the coming year’s Foley Music and Arts Studio policy (for reference, here is my current 2019-20 studio policy):

The rate issue. Don’t cut your rates unless you absolutely have to. Your value as a music teacher is more important than ever and you need to come across as a professional. The range of extra-curricular activities might be much smaller than before, especially without team sports or large ensembles. On the other hand, avoid raising your rate beyond a small amount lest people accuse you of price-gouging in a pandemic. We intend to keep our rates the same.

Equivalency of online and in-person lessons. In order to maintain stability of income and scheduling with your studio in the face of future risk, there needs to be a one-to-one correspondence between in-person and online lessons. They should be interchangeable.

Sickness policies. If students are sick, they should not get an in-person lesson. On the other hand, if they’re already comfortable with online lessons, they can continue in their regular lesson times online if they’re well enough and until they’re back to full health.

How to describe management of the transition back to in-person lessons. Each of us is hoping to be able to teach in-person by the fall. However, we must also account for the eventuality that there might be a second wave of the virus precipitating further lockdowns in your area.

Things you can and cannot bring into the studio space. One of my professional students has already laid out a policy that students need to bring their own soap and towel to wash their hands in the studio. On the other hand, I no longer feel comfortable with people bringing in stuff to the studio beyond their books and music.

Adherence to new health and safety procedures in the studio. Rebekah Maxner’s article on health-proofing your studio is the best article I’ve seen in this area. Distancing, use of masks, hand-washing, and limitations of in-studio touching all need to be considered.

What to mention in the studio policy and what to mention via email updates. One possibility is to mention health and safety procedures in a general sense, then elaborate on them via email as you get closer to the beginning of the teaching year. Then further update them through the year as the situation warrants.

Above all, communicate how to facilitate structured learning through a time of uncertainty. Stating clear policies with relevant updates can put you ahead of many other extra-curricular activities (and school districts).

I’ve already taken some heat for “perpetuating fear and anxiety” and “throwing tradition out the window” when talking about current realities of the piano studio (members of Facebook’s Piano Teacher Central can find the comments here). But it is vitally important that we communicate to our customer base how we intend to engage with health and safety issues in the coming year. Far from being disrespectful to the tradition of musical instruction, dealing with health issues in the middle of a global pandemic goes to the heart of our mission and professionalism.